Aaron Sue

Edited by: Julia Poncela

Instructing students can come in multiple forms, and each has its own benefits and pitfalls. As I have been assigned to lead two laboratory sections for an undergraduate biology lab, I would like to share some of my experiences in the few weeks I have been teaching, as well as some of the lessons I have learned. I have the advantage (or perhaps challenge) of instructing very disparate class personalities; one of my labs has a majority of students who are a part of an accelerated science program, while the other does not. Even in three weeks, this has given me an appreciation for what most teachers/professors have to go through: communicating information to a wide distribution of individuals. Here a few things I think are crucial to consider:

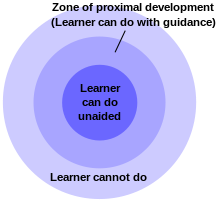

Assume your students know nothing. As harsh as this sounds, in a setting where learning is based on a hands-on approach, such as lab courses or mentorship (like grad students teaching undergrads, etc), detail is critical. Often, the student learns by following some protocol or has to design an experiment to test a system. In these cases, the level of instruction given will determine the success of the student. Obviously, you can’t expect to essentially throw someone into the deep end and expect them not to sink, but at the same time you can’t expect someone to learn to swim by sitting in the kiddie pool all day. Personally, I find the developmental theory of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) to be extremely applicable in this case. In short, you have three areas of tasks, as depicted in the figure shamelessly stolen from Wikipedia:

The innermost circle provides no benefit because the learner already has this skillset to accomplish whatever task he/she is assigned. Likewise, the outermost circle is useless because the learner has no skillset to even attempt any task. The ZPD is unique in that the learner has the tools to solve a problem, however he/she simply needs a guide to put the right pieces together. Coming back to my original point, assuming your student knows nothing I think is much better, as it is easier to learn to swim starting from the shallow end and going out deeper, rather than the opposite. If you start out with the most difficult tasks, gaps are inevitably made as they most likely have no idea what you are talking about, and miss any significance of what they are learning. The most crucial part becomes where do you base your “shallow end” from, so finding the ZPD is rapid and the student can maximize his/her learning potential.

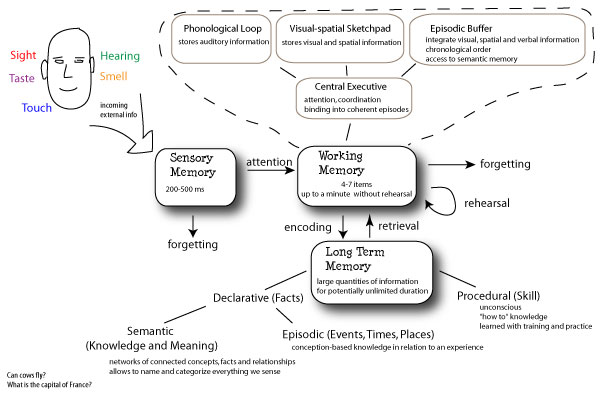

Repetition will cement knowledge and seal cracks. After a student has demonstrated that he/she can perform a certain task, it is worth repeating the task (in some form or another) to really make sure that the learner has true mastery over what was just learned. This is also can be an indicator if something was incorrectly learned and gives the teacher an opportunity to correct it. Again taking a psychology approach, here is a slightly creepy figure of memory encoding:

There are two important pathways here: rehearsal and retrieval. The output from working memory has two possible outcomes, encoding or forgetting. It is not safe to assume that a student has learned something after demonstrating it once, and rehearsal ensures that it will become encoded. Likewise, to make sure that a long term memory does not degrade over time, retrieval (another form of rehearsal) can also be effective in solidifying knowledge. Also, as I had mentioned these repeats serve not only as a method for solidifying learned material, but also as a checkpoint for the instructor to monitor the quality of the knowledge. I found that misunderstandings seem to slip through more often than I thought, as evidenced through quiz/worksheet grading. Certainly, I plan on reiterating these topics in the few weeks that I have, as well as testing my students with similar (yet progressively more difficult) questions to reinforce what they have learned.

There will be accidents. Thinking that anything will go over smoothly is foolish, and when you think that something is completely accident-proof, you will be pleasantly surprised. Being prepared for such moments is a trial itself, but in the end it could help salvage potentially wasted time starting over again. Knowing where things could go wrong is also critical, as being able to explain errors to your protégé can teach them something as well. In theory, a perfectly executed lesson/experiment can be less beneficial than one that was struggled through tooth and nail. This can grant students a true appreciation for what they have learned, as knowing how something works is only the half of it. Additionally, with the expectation of mishaps (although seemingly pessimistic), having a positive attitude about it will make the students feel better, as they will be beating themselves up enough (if they care). To quote an old friend, “Negative attitudes lead to negative results.” Certainly, if they are doom and gloom they will perform worse and lose their patience easier, so keeping them enthusiastic can make even major catastrophes a positive learning experience. No experience is the same. Although I have listed a few things I think are broadly applicable to any teaching role, as the title implies, there is no formula for education (so why did I even bother listing anything)? Let each opportunity be a new lesson for yourself as well; you are bound to encounter every personality in the spectrum. Like my last point says, be ready to adapt and readjust on the spot, or you will quickly lose the interest of your students. Most importantly, be engaged and invested in their learning, nothing turns off a student faster than an unenthusiastic instructor.Thanks for surviving my first post!

~Aaron